Plants of Our Mountain Community

Our Forests

By Lynn Stafford, Liz Buchroeder and Bill Buchroeder

Photos by Bill Buchroeder, Liz Buchroeder, Maryann Ryan, Mary McDevitt and Lynn Stafford

Trees are all around us here in PMC. But what are they? Are they individual organisms locked in a to-the-death struggle with each other and all other creatures? This is the classic competition model for existence in nature. Each living thing is in a battle with other living things for life. Or is the situation more complex? Recent research has shown that there are intricate networks of roots and fungal strands in the soil connecting trees and other plants. These are called “mycorrhizal associations.” Chemical analysis including using radioactive isotopes to trace movement of materials have shown that these organisms pass water, food and minerals back and forth along the network. The fungal strands create the connection between root systems and provide minerals and water to the roots. The plants supply food to the fungi. And there is even evidence that neighboring trees of different species share resources.

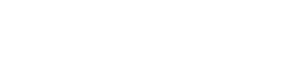

Figure 1: Canyon live oak with Randy Cushman

Figure 1 shows a mature canyon live oak with young pinyon pines and oaks underneath it (note the hiker for size comparison). Is this a “mother tree” providing shade and nourishment to these youngsters? Scientific studies indicate that this might well be true. Elder trees may be the hub of mycorrhizal transportation and communication between trees. This concept presents an entirely different way of viewing the forest. It is already known that trees can communicate bark beetle outbreaks and other traumas to their neighbors. Now, research indicates that there may be intricate communication and transportation networks within a forest. Instead of nerve ganglia and axons, as in animal nervous systems, there are underground root and fungal pathways.

Figure 2: Jim Whitener Tree with Lynn Stafford and Liz Buchroeder

Current forest management practices, such as clear-cutting and removal of elder trees, may be counterproductive. It is likely that members of the forest exist in a finely tuned system that benefits all the inhabitants. We humans know little of this world that is hidden in plain sight. We tend to give artificial values to trees. Is it commercially valuable? Does it look old and scarred? Is it just a dead snag? I will now focus on a few wonderful trees in PMC.

The Jim Whitener ponderosa pine (Figure 2) is our best-known and largest tree. It stands close to Mil Potrero Highway in the Yellowstone Drive area, but is difficult to reach on foot. It appears quite healthy, although it lost its top a few years ago. The diameter near the base is 6 feet, 8 inches. Age estimates go from 400 years on up. We have two three-needle pine trees known as yellow pines in PMC. The common species here is the Jeffrey pine. The Whitener Tree, plus a few other large ponderosas, may be remnants from a cooler and wetter past.

Near the Whitener tree was a large ponderosa pine that lived next to the highway. It died and became a standing snag. The snag was cut down in 2018 because of the danger to the road. I, along with friends, measured the trunk and counted the tree rings (Figure 3). This one lived for more than 250 years. It was growing before any of the local mountain communities existed.

Figure 3: Counting ponderosa pine annual rings – Randy Cushman, Lynn Stafford, Mary McDevitt

Figure 4: Lightning strike scar on Jeffrey pine

Jeffrey pines are found throughout the higher and cooler portions of PMC. The large pines around the Business Center are Jeffreys. Figure 4 shows one of the ordeals a tall tree must endure – lightning strikes. Lightning often travels down the outside of the trunk in the living tissue immediately below the bark, producing a linear scar. Jeffrey pines also provide homes for many animals. This great horned owl and her mate raised a family of two young in a Jeffrey pine close to the Post Office in 2018 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Great horned owl on Jeffrey pine

Single-leaf pinyon pine is our most common, and least-appreciated, conifer. It doesn’t grow very tall, is grayish blue in color and often does not look very majestic (Figure 6). However, pinyons are extremely important trees in our mountains. They occupy dry, hot slopes shunned by other conifers. Their rich pine nuts are favored by many animals and humans, alike. Their foliage offers hunting for insect-eating birds, such as the mountain chickadee (Figure 7).

Figure 6: Pinyon pine

Figure 7: Pinyon pine foliage with mountain chickadee

There is a conifer tree in PMC that has been seen by very few people. It resides in an inconspicuous, little-visited canyon. It is a particularly large specimen (6 feet, 8 inches in diameter) of an unusual species called the bigcone Douglas-fir (Figure 8). This tree is only found in Southern California. This giant thrives unseen within our community. PMC is still able to provide sanctuary for portions of the natural world.

Figure 8: Bigcone Douglas-fir with Edie Stafford and Jim Lockhart

Figure 9: Valley oak showing rounded lobed leaves and long, pointed acorns

Lastly, I would like to recognize a tree that does not occur in PMC but is found in our mountains. This is the valley oak (Figure 9). The Community Park in Frazier Park has a heritage grove of venerable oldsters. Some community activists are working to protect these trees and young saplings appearing around them. The great horned owl is one of many birds inhabiting these oaks. This mother owl is protecting two fluffy youngsters nearby (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Valley oak with great horned owl

Plants of the San Emigdio Mountains Region of California by Pam De Vries discusses these and other local trees. It can be purchased at AdventureInk bookstore in PMC Business Center. Mycorrhizal associations are thoroughly covered in Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard.

---------------------------------------------------------

Plants Can Have Relationships, Too!

By Lynn Stafford, Liz Buchroeder and Bill Buchroeder

Photos by Bill Buchroeder, Liz Buchroeder, Charles Noble, Maryann Ryan, David Schindler and Lynn Stafford

Those of us who enjoy nature tend to think of different plants and animals as discreet entities. As we walk the trails, we note the cottontail bunny, the bluebird, various flowers, different species of trees. However, there is much going on that brings these different organisms into meaningful contact with each other. One aspect of the complexity of plants and animals is their ability to form partnerships with other organisms. I am going to describe four of these relationships that occur locally in our mountains.

Figure 1: Male phainopepla on scrub oak

Fig. 2: Female phainopepla on scrub oak

Phainopepla/mistletoe: An interesting bird that is found locally, but can be difficult to glimpse, is the phainopepla. It looks like a black cardinal with white wing patches (Fig. 1), (Fig. 2). The phainopepla prefers mistletoe berries for food. In our area, it frequents mistletoe on oak trees (Fig. 3). How does it help mistletoe? When it defecates, it often deposits its “poop” on branches of the oak tree. The gut of the phainopepla has softened the skin of the mistletoe berry, the “poop” acts as fertilizer and the baby mistletoe finds another foothold into the oak tree. This relationship is not doing the oak tree any good, but it is a satisfactory partnership for the bird and the mistletoe.

Fig. 3 Mistletoe on scrub oak

Acorn woodpecker/oak tree: Now we come to a relationship that benefits the oak tree. Acorn woodpeckers are the noisy, gregarious woodpeckers that sometimes cause damage to houses here in our mountains (Fig. 4). They don’t mean to be harmful. They simply are storing acorns for later use (Fig. 5). They are absolutely dependent on several species of oak. They return the favor by accidentally dropping acorns well away from the oak tree. Acorns are heavy and will drop straight down. The woodpecker gives them a longer ride, hopefully where they can germinate.

Fig. 4: Acorn woodpecker

Fig. 5 Acorn woodpecker with its acorn cache

Jays/pinyon pine: For another example of bird and tree helping one another, we come to loud, obvious jays and a very common pine tree. The single-leaf pinyon pine is the prominent pine tree thriving on our drier slopes, frequently on the south sides of our mountains. Both California scrub-jay (Fig. 6) and Steller’s jay (Fig. 7) are attracted to the large nutritious nuts of this pine. Having a different style of food storage than the acorn woodpecker, these jays bury their nuts in many different places in soft humus soil. This is ideal for the reproductive success of the pinyon pine, because, as smart as jays are, they will forget where they stored some of their nuts.

Fig. 6: California scrub-jay with a pine nut

Fig. 7: Steller’s jay in a pinyon pine with a pine nut

Paintbrush/sagebrush/penstemon: (Fig. 8) shows paintbrush, an attractive flower in our open woods. (Fig, 9) includes three plants, the paintbrush, the blue Grinnell’s penstemon and the gray foliage of sagebrush. Paintbrush is a partially dependent parasite on the root systems of several bush species, in this case, probably the sagebrush. It generally does not hurt the host very much. (Fig. 10) displays the penstemon again, this time in association with a pollinating native bumble bee. Here, the flower feeds the bumble bee nectar (sugar) and pollen (protein), while the bee carries fertilizing pollen from one flower to another. So, we have two relationships between these three plants and one insect. Maybe more complex relationships are hidden in there, somewhere.

Fig. 8: Paintbrush

Fig. 9: Paint brush, Grinnell’s penstemon and sagebrush

These are just a few examples of the complexity of the natural world around us. Do go outside and enjoy these wonders.

Fig. 10 Grinnell’s penstemon with a California bumble bee

---------------------------------------------------------

Showy Flowers in our High Mountains

By Lynn Stafford, Liz Buchroeder and Bill Buchroeder

Photos by Liz Buchroeder, Bill Buchroeder, Mary McDevitt and Randy Cushman

Spring and summer come later on the peaks and ridges above PMC than down here in our village. Residences in PMC range from 4,900' to 6,400' in elevation. San Emigdio Mountain to the north of us rises to a little over 7,000'. Immediately to the south of our community are several peaks over 8,000', with Mt. Pinos being almost 9,000'. July is a good time to visit the higher country for flowers and other outdoor enjoyments. Two paved roads lead to the Mt. Pinos and Cerro Noroeste high country. This article will focus on some of the more attractive wildflowers. A future article will discuss other aspects of our mountains.

Fig. 1: Western Blue Flag Iris

Close to the upper end of the Mt. Pinos Road is a lush meadow, a rarity in these mountains. One of the stand-out features is the wild iris known as western blue flag (Fig. 1). Before we proceed further, why flowers? And why are they so showy? The answer is to attract insects and a few other animals. The flowers offer nutritious nectar and pollen, and the feeding animals pass the pollen on from plant to plant, facilitating reproduction of the plants. Flowering plants and insects have evolved in unison over many millions of years.

Fig. 2: Bumblebee on Blue Flag Iris

The bumblebee working a blue flag is an industrious example (Fig. 2). Please do not trample the meadow while observing the flowers. It is fragile.

Fig. 3: Mexican Pink flower

Sometimes, plant names have interesting backgrounds. The Mexican pink (Fig. 3) is sort of pinkish in color, but that is not the source of the name. As people who work with clothes can tell us, a pinking shear cuts a zig-zag pattern in fabric, just like the tips of these flower petals. Another odd name is the western wallflower (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Western Wallflower

Of course, a person is called a wallflower because he/she is shy, standing at the edge of the dance floor, not taking part. The wallflower plant is known for occurring either solitarily or in very small numbers. Their bright yellow can be seen occasionally on the sides of our mountain roads.

Fig. 5: Sierra Snow Plant

Now we come to two strange characters. Most flowering plants make their food through photosynthesis in their green leaves. But, there are exceptions. The Sierra snow plant (Fig. 5), named because it often emerges shortly after snow melt, has no greenery, produces no food and derives its nutrition indirectly from tree roots.

Fig. 6: Paintbrush

Paintbrush (Fig. 6) is another showy flower that, at least partially, relies on other plants for its nutrition. Paintbrushes are often found with sagebrush. Any attempt to dig up and transplant a wild paintbrush will yield only failure, because the host will not be present.

Fig. 7: Lupine

Two showy blue wildflowers are the lupine (Fig. 7) and the showy blue penstemon (Fig. 8). It may be tempting to think that they are being so attractive for our benefit, but, in reality, it is all about the insect pollinators.

Fig. 8: Showy Blue Penstemon

There are several local lupine species, growing in a variety of habitats. One interesting species is named the grape-soda lupine. Sometimes, plant taxonomists can have a bit of fun. The showy blue penstemon is also named creatively. It is found throughout a range of elevations in open areas.

Fig. 9: Seep-spring Monkeyflower

Next are two hard-to-overlook flowers in the yellow-to-orange color range. The seep-spring monkeyflower (Fig. 9) gives away its habitat with its name. Its feet are always wet. One of my favorite local flowers is the Kennedy’s mariposa lily (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10: Kennedy's Mariposa Lily

There are several lovely mariposa species in our area. Did you know that mariposa means butterfly in Spanish?

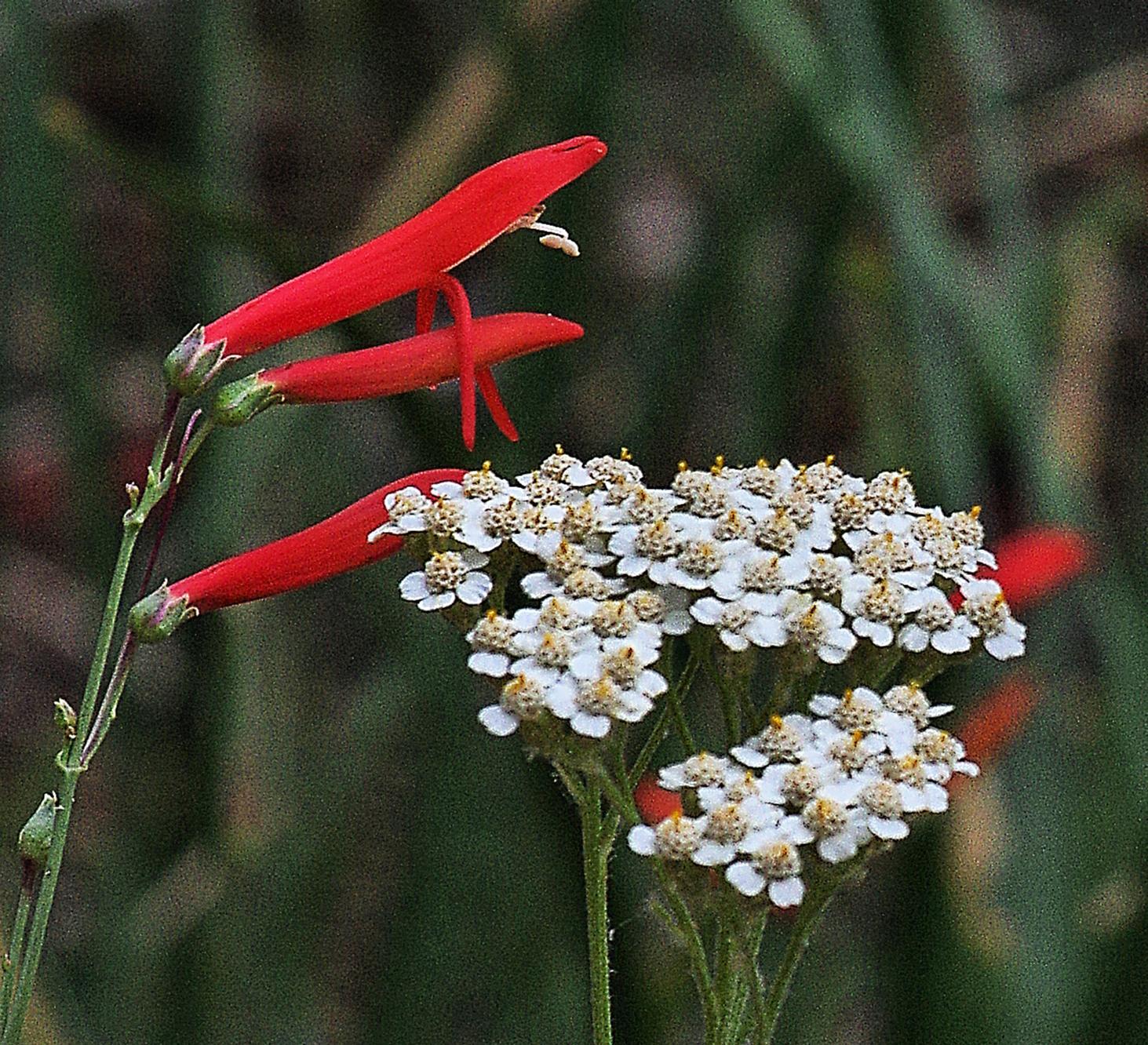

Fig. 11: Common Yarrow/Southern Scarlet Penstemon

(Fig. 11) is an artistic photographer’s creation. My friend, Randy Cushman, captured this duet of color and form up on Mt. Pinos. The white comes from common yarrow. The bright red is the southern scarlet penstemon.

I hope you all find time to enjoy our High Mountain beauties. For more information on our local flora, check out the excellent book, Plants of the San Emigdio Mountains Region of California by local professional botanist, Pam De Vries. This book can be purchased at Adventure Ink, a bookstore in PMC’s Business Center.